“While each of our individual companies serves its own corporate purpose, we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders.”

With this sentence, the US Business Roundtable, which represents the chief executives of 181 of the world’s largest companies, abandoned their longstanding view that “corporations exist principally to serve their shareholders”.

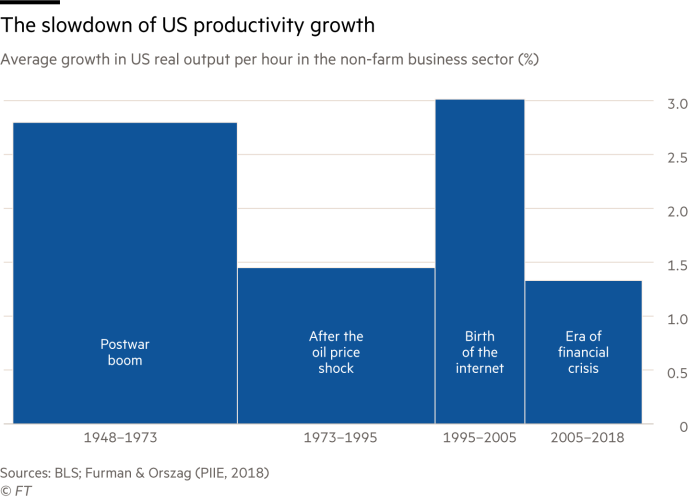

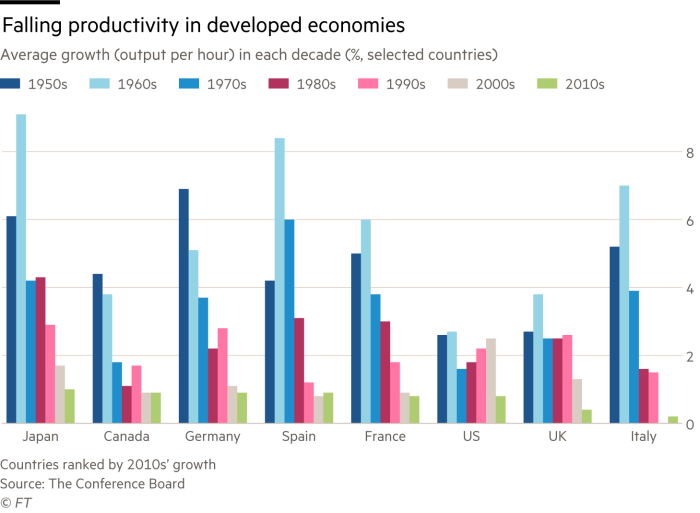

This is certainly a moment. But what does — and should — that moment mean? The answer needs to start with acknowledgment of the fact that something has gone very wrong. Over the past four decades, and especially in the US, the most important country of all, we have observed an unholy trinity of slowing productivity growth, soaring inequality and huge financial shocks.

As Jason Furman of Harvard University and Peter Orszag of Lazard Frères noted in a paper last year: “From 1948 to 1973, real median family income in the US rose 3 per cent annually. At this rate . . . there was a 96 per cent chance that a child would have a higher income than his or her parents. Since 1973, the median family has seen its real income grow only 0.4 per cent annually . . . As a result, 28 per cent of children have lower income than their parents did.”

So why is the economy not delivering? The answer lies, in large part, with the rise of rentier capitalism. In this case “rent” means rewards over and above those required to induce the desired supply of goods, services, land or labour. “Rentier capitalism” means an economy in which market and political power allows privileged individuals and businesses to extract a great deal of such rent from everybody else.

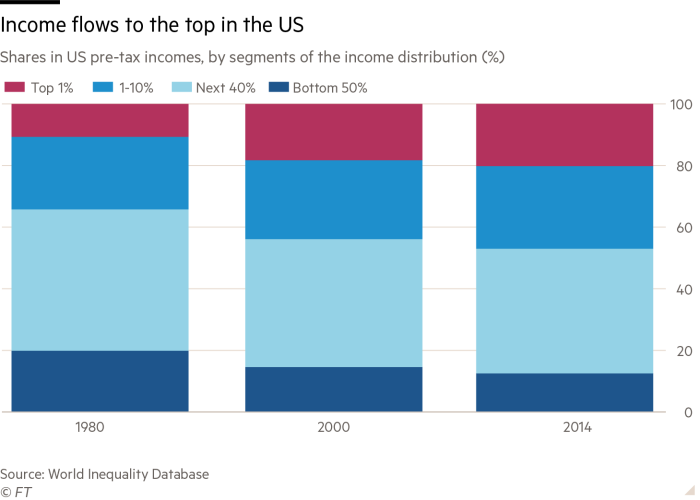

That does not explain every disappointment. As Robert Gordon, professor of social sciences at Northwestern University, argues, fundamental innovation slowed after the mid-20th century. Technology has also created greater reliance on graduates and raised their relative wages, explaining part of the rise of inequality. But the share of the top 1 per cent of US earners in pre-tax income jumped from 11 per cent in 1980 to 20 per cent in 2014. This was not mainly the result of such skill-biased technological change.

If one listens to the political debates in many countries, notably the US and UK, one would conclude that the disappointment is mainly the fault of imports from China or low-wage immigrants, or both. Foreigners are ideal scapegoats. But the notion that rising inequality and slow productivity growth are due to foreigners is simply false.

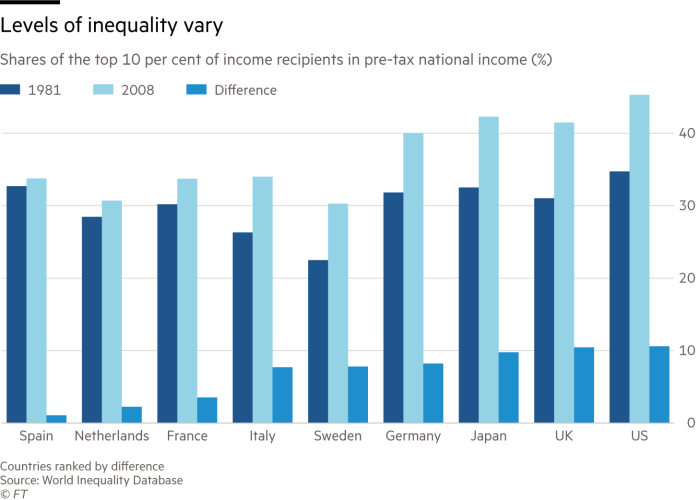

Every western high-income country trades more with emerging and developing countries today than it did four decades ago. Yet increases in inequality have varied substantially. The outcome depended on how the institutions of the market economy behaved and on domestic policy choices.

Harvard economist Elhanan Helpman ends his overview of a huge academic literature on the topic with the conclusion that “globalisation in the form of foreign trade and offshoring has not been a large contributor to rising inequality. Multiple studies of different events around the world point to this conclusion.”

The shift in the location of much manufacturing, principally to China, may have lowered investment in high-income economies a little. But this effect cannot have been powerful enough to reduce productivity growth significantly. To the contrary, the shift in the global division of labour induced high-income economies to specialise in skill-intensive sectors, where there was more potential for fast productivity growth.

Donald Trump, a naive mercantilist, focuses, instead, on bilateral trade imbalances as a cause of job losses. These deficits reflect bad trade deals, the American president insists. It is true that the US has overall trade deficits, while the EU has surpluses. But their trade policies are quite similar. Trade policies do not explain bilateral balances. Bilateral balances, in turn, do not explain overall balances. The latter are macroeconomic phenomena. Both theory and evidence concur on this.

The economic impact of immigration has also been small, however big the political and cultural “shock of the foreigner” may be. Research strongly suggests that the effect of immigration on the real earnings of the native population and on receiving countries’ fiscal position has been small and frequently positive.

Far more productive than this politically rewarding, but mistaken, focus on the damage done by trade and migration is an examination of contemporary rentier capitalism itself.

Finance plays a key role, with several dimensions. Liberalised finance tends to metastasise, like a cancer. Thus, the financial sector’s ability to create credit and money finances its own activities, incomes and (often illusory) profits.

A 2015 study by Stephen Cecchetti and Enisse Kharroubi for the Bank for International Settlements said “the level of financial development is good only up to a point, after which it becomes a drag on growth, and that a fast-growing financial sector is detrimental to aggregate productivity growth”. When the financial sector grows quickly, they argue, it hires talented people. These then lend against property, because it generates collateral. This is a diversion of talented human resources in unproductive, useless directions.

Again, excessive growth of credit almost always leads to crises, as Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff showed in This Time is Different. This is why no modern government dares let the supposedly market-driven financial sector operate unaided and unguided. But that in turn creates huge opportunities to gain from irresponsibility: heads, they win; tails, the rest of us lose. Further crises are guaranteed.

Finance also creates rising inequality. Thomas Philippon of the Stern School of Business and Ariell Reshef of the Paris School of Economics showed that the relative earnings of finance professionals exploded upwards in the 1980s with the deregulation of finance. They estimated that “rents” — earnings over and above those needed to attract people into the industry — accounted for 30-50 per cent of the pay differential between finance professionals and the rest of the private sector.

This explosion of financial activity since 1980 has not raised the growth of productivity. If anything, it has lowered it, especially since the crisis. The same is true of the explosion in pay of corporate management, yet another form of rent extraction. As Deborah Hargreaves, founder of the High Pay Centre, notes, in the UK the ratio of average chief executive pay to that of average workers rose from 48 to one in 1998 to 129 to one in 2016. In the US, the same ratio rose from 42 to one in 1980 to 347 to one in 2017.

As the US essayist HL Mencken wrote: “For every complex problem, there is an answer that is clear, simple and wrong.” Pay linked to the share price gave management a huge incentive to raise that price, by manipulating earnings or borrowing money to buy the shares. Neither adds value to the company. But they can add a great deal of wealth to management. A related problem with governance is conflicts of interest, notably over independence of auditors.

In sum, personal financial considerations permeate corporate decision-making. As the independent economist Andrew Smithers argues in Productivity and the Bonus Culture, this comes at the expense of corporate investment and so of long-run productivity growth.

A possibly still more fundamental issue is the decline of competition. Mr Furman and Mr Orszag say there is evidence of increased market concentration in the US, a lower rate of entry of new firms and a lower share of young firms in the economy compared with three or four decades ago. Work by the OECD and Oxford Martin School also notes widening gaps in productivity and profit mark-ups between the leading businesses and the rest. This suggests weakening competition and rising monopoly rent. Moreover, a great deal of the increase in inequality arises from radically different rewards for workers with similar skills in different firms: this, too, is a form of rent extraction.

A part of the explanation for weaker competition is “winner-takes-almost-all” markets: superstar individuals and their companies earn monopoly rents, because they can now serve global markets so cheaply. The network externalities — benefits of using a network that others are using — and zero marginal costs of platform monopolies (Facebook, Google, Amazon, Alibaba and Tencent) are the dominant examples.

Another such natural force is the network externalities of agglomerations, stressed by Paul Collier in The Future of Capitalism. Successful metropolitan areas — London, New York, the Bay Area in California — generate powerful feedback loops, attracting and rewarding talented people. This disadvantages businesses and people trapped in left-behind towns. Agglomerations, too, create rents, not just in property prices, but also in earnings.

Yet monopoly rent is not just the product of such natural — albeit worrying — economic forces. It is also the result of policy. In the US, Yale University law professor Robert Bork argued in the 1970s that “consumer welfare” should be the sole objective of antitrust policy. As with shareholder value maximisation, this oversimplified highly complex issues. In this case, it led to complacency about monopoly power, provided prices stayed low. Yet tall trees deprive saplings of the light they need to grow. So, too, may giant companies.

Some might argue, complacently, that the “monopoly rent” we now see in leading economies is largely a sign of the “creative destruction” lauded by the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter. In fact, we are not seeing enough creation, destruction or productivity growth to support that view convincingly.

A disreputable aspect of rent-seeking is radical tax avoidance. Corporations (and so also shareholders) benefit from the public goods — security, legal systems, infrastructure, educated workforces and sociopolitical stability — provided by the world’s most powerful liberal democracies. Yet they are also in a perfect position to exploit tax loopholes, especially those companies whose location of production or innovation is difficult to determine.

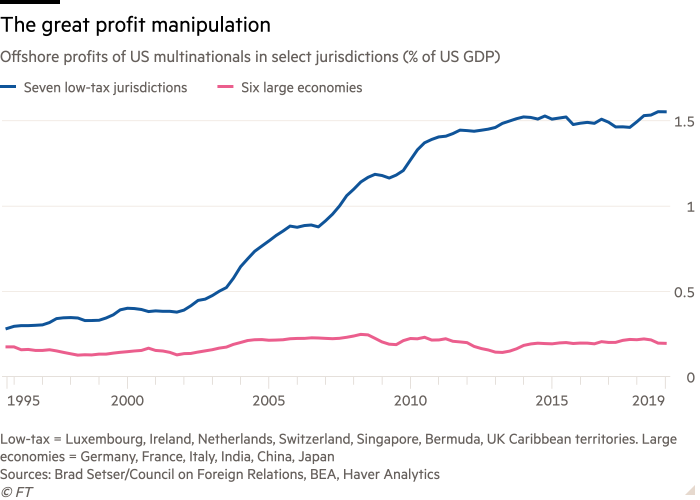

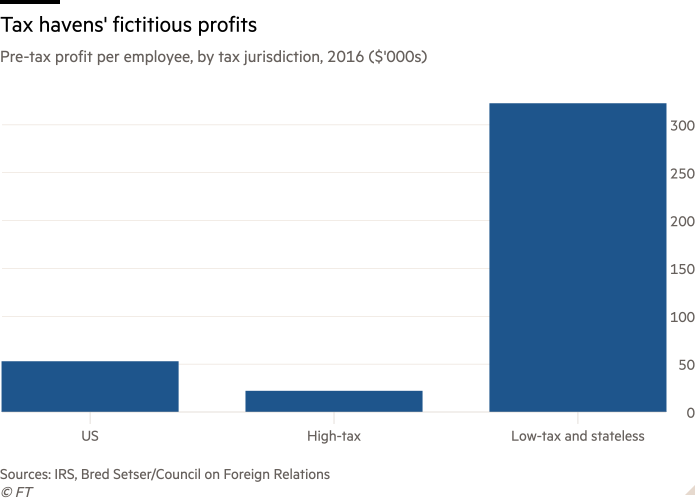

The biggest challenges within the corporate tax system are tax competition and base erosion and profit shifting. We see the former in falling tax rates. We see the latter in the location of intellectual property in tax havens, in charging tax-deductible debt against profits accruing in higher-tax jurisdictions and in rigging transfer prices within firms.

A 2015 study by the IMF calculated that base erosion and profit shifting reduced long-run annual revenue in OECD countries by about $450bn (1 per cent of gross domestic product) and in non-OECD countries by slightly over $200bn (1.3 per cent of GDP). These are significant figures in the context of a tax that raised an average of only 2.9 per cent of GDP in 2016 in OECD countries and just 2 per cent in the US.

Brad Setser of the Council on Foreign Relations shows that US corporations report seven times as much profit in small tax havens (Bermuda, the British Caribbean, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Singapore and Switzerland) as in six big economies (China, France, Germany, India, Italy and Japan). This is ludicrous. The tax reform under Mr Trump changed essentially nothing. Needless to say, not only US corporations benefit from such loopholes.

In such cases, rents are not merely being exploited. They are being created, through lobbying for distorting and unfair tax loopholes and against needed regulation of mergers, anti-competitive practices, financial misbehaviour, the environment and labour markets. Corporate lobbying overwhelms the interests of ordinary citizens. Indeed, some studies suggest that the wishes of ordinary people count for next to nothing in policymaking.

Not least, as some western economies have become more Latin American in their distribution of incomes, their politics have also become more Latin American. Some of the new populists are considering radical, but necessary, changes in competition, regulatory and tax policies. But others rely on xenophobic dog whistles while continuing to promote a capitalism rigged to favour a small elite. Such activities could well end up with the death of liberal democracy itself.

Members of the Business Roundtable and their peers have tough questions to ask themselves. They are right: seeking to maximise shareholder value has proved a doubtful guide to managing corporations. But that realisation is the beginning, not the end. They need to ask themselves what this understanding means for how they set their own pay and how they exploit — indeed actively create — tax and regulatory loopholes.

Read more by Martin Wolf

They must, not least, consider their activities in the public arena. What are they doing to ensure better laws governing the structure of the corporation, a fair and effective tax system, a safety net for those afflicted by economic forces beyond their control, a healthy local and global environment and a democracy responsive to the wishes of a broad majority?

We need a dynamic capitalist economy that gives everybody a justified belief that they can share in the benefits. What we increasingly seem to have instead is an unstable rentier capitalism, weakened competition, feeble productivity growth, high inequality and, not coincidentally, an increasingly degraded democracy. Fixing this is a challenge for us all, but especially for those who run the world’s most important businesses. The way our economic and political systems work must change, or they will perish.

About Martin Wolf

As the FT’s chief economics commentator, Martin Wolf paints on a wide canvas. He focuses on the world economy, and has paid particular attention to globalisation, financial crises and, more recently, trade wars. Pro-market but pragmatic, he ranges broadly and skilfully from the challenge of climate change to the rise of populism, and even the prediction that interest rates would remain very low for a very long time.

The FT is free to read today. You can share this article using the buttons at the top.

Get alerts on Capitalism when a new story is published

novalier

Fourier

L

Custom HTML Preview

The signs being carried on the streets in New York in late 2008 read "Bail Me Out". The seeds of the current problem are to be found in the bailouts after the financial crisis and the failure then to bring criminal activity to account: the latter because, according to Bernanke, the then US Treasury Secretary was frightened of squashing the financial sector. True capitalism allows failed enterprises to be replaced by new, healthy ones. But the cleaning mechanism was not allowed to operate. The problem arises from the fact that we don't live in a capitalist system any more.

Yves Smith always has something invaluable to add to the conversation. Its an honor and privilege to be her messenger!

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2019/09/the-financial-times-martin-wolf-discovers-that-rentier-capitalism-and-financialization-increase-inequality-and-hurt-growth.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed:+NakedCapitalism+(naked+capitalism)

StephenKMackSD

Wise words: 'Liberalised finance tends to metastasise, like a cancer. Thus, the financial sector’s ability to create credit and money finances its own activities, incomes and (often illusory) profits.'

Good to see Mr. Wolf finally noticed reality, a couple of decades late.

Regulatory arbitrage is systemic and the Big 4 global firms are at the heart of it unfortunately. Research which may help https://www.academia.edu/19497525/KPMGS_REGULATORY_ARBITRAGE_CULTURE

«So why is the economy not delivering? The answer lies, in large part, with the rise of rentier capitalism.»

The really important political detail is being missed: if rentierism were not delivering at all, it would be very politically unpopular, but it it is quite politically popular because it does deliver stunning amounts of redistribution and state welfare in favour of a large minority of rentiers, extracted from everybody else.

That's the big challenge, the political problem: the rentiers are not just the 0.1% who try to subvert democracy, the rentiers are the 20-30% who own significant amounts of shares and property where it is government policy to redistribute to share and property rentiers big and small.

For example in the UK the political problem is the millions of voters who thanks to Thatcher's and Blair's and Osborne's policies have made £30,000-£40,000 a year in work-free tax-free gain every year for over 30 years from their southern properties and share accounts, entirely unproductively and at the expense of renters and buyers, and these millions of voters absolutely want that to continue at any cost to someone else; these millions of voters think they are on the same side as the 0.1% working in the finance and property industries who extract fantastic amounts of unproductive income from everybody else too.

These people know very well that the only reason they are able to extract such fantastic amounts without producing anything (and the finance and property industries most likely are in the aggregate subtrative not merely unproductive) is government intervention in their favour, and so they vote religiously and fund the campaigns of the parties that protect their extractive interests.

@Mandrocles Yep, or to summarise, to focus on the 1% is to miss the point. The upper 25% have much to lose and would rather not.

Still leaves 75% who aren't very good at making themselves heard. Their best effort was voting Trump/Brexit and neither will help at all.

It will be interesting to see whether the wholesale embrace of radical SJW wokeness by many corporations recently, which has the maximum public performative value, but provides the minimum challenge to the fundamental economic status quo, will be successful in difusing this issue i.e. whether the bait and switch of putting an already successful woman on a company board or sponsoring at relatively low cost an LBGQT event is sufficient to placate public anger at stagnating wages, rising costs and an increasingly feudal society.

One senses with Trump and Brexit that this behaviour will, in the long run, only compound the issue, but contemporary politics suggests that the Left is completely deaf to that reality.

"No ‘guts,’ no sense, no vision! A terrible communicator!”

Words tweeted yesterday by The Sociopath of Our Time.

Much more relevant to the contents of this dreary article, the contents of which any well-informed person is already aware of.

This sentiment is not mine alone.Look at many of the Comments that precede this.

For those of us who neither have the time nor the resources to assemble a vital few prescriptions / proscriptions as to how to meaningfully extricate ourselves from the self-destructive trajectory as described, please, please spare us the hand-wringing platitudes that reach an all-time crescendo in the very last sentence of this piece.

Great article Mr. Wolf summarizing in an understandable way many important matters.

Here a short interview with the economist Prof. Richard Werner, in a similar manner highlighting brillantly the situation of the financial sector.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EC0G7pY4wRE

Dear Mr. Wolf,

While all of the issues you are raising in your article have contributed to the deterioration of capitalism into its current rigged form - chiefly the forming of corporate oligopolistic power through industry consolidation and (US tech) monopolisation - you are avoiding to discuss the role endless QE has played in all this over the past decade.

Could it be that this is because you have been one of its biggest cheerleaders over the years?

The target of QE is to manipulate asset prices up (it does NOT contribute to economic growth, see e.g. the writings of John Hussman and others), and the only beneficiaries are obviously those who did already own these assets, and a strengthening of those who have access to the ultra cheap capital this creates. While QE is clearly useful as a short term emergency measure, unelected central bankers are still employing this misguided monetary policy 11 years after the GFC.

QE was also explicitly chosen - after intense lobbying of bank management teams - to avoid having to restructure (i.e wipe out the equity of) banks. The same goes for a number of other sectors (with the exception of the US car industry probably).

The result is that the key mechanism of capitalism - weeding out the weak - has been suspended; that these old (bank) management teams are still in place, with their power enhanced; that "zombie" companies survived avoiding capacity reduction in a number of sectors; misallocation of cheap capital on a grand scale; soaring house prices globally (impoverishing the large portion of those who rent); debt fueled share buybacks in the US; a focus on M&A financed with cheap debt and thus even further industry consolidation and oligopolisation across all sectors; and record corporate profitability that in the old days would have been competed away but does not anymore.

@MR Add to that the way in which QE and Central Bank regulations favour private equity and private credit investors to the detriment of SMEs. Notably, high percentages of SMEs report difficulty accessing credit from banks for investment and working capital needs while larger multinationals and private equity investors access credit at exceptionally low rates relative to their credit risk profile.

This is a deliberate and perverse policy deployed by central banks because those top decision makers in Central Banks know that their future income and advisory fees will come from those large asset managers that are most benefitting from this corrupt policy.

A superb article. Should be read by everyone. Thank you, Mr Wolf.

Very wide-sweeping, poorly argued points that all sound lovely but don't really mean very much. Where has Mr. Wolf identified a problem that needs to be addressed? He's raised lots of 'issues' that are fashionably problems to be fixed, without any sort of rigorous analysis of why these points - income inequality, low levels of corporate tax participation, dominance of certain industries by certain companies - actually need fixing.

Speckled with sweet sounding sound bites, but nothing intellectual in this article at all.

Yes

@PseudonymAeruginosa Sees to me there are three actions which could start to reverse the continued accumulation of resources by the few; first is to change the guidance for competition authorities to insist on greater competition - if a "natural monopoly" exists then it must be regulated, second to rule that intellectual property must belong to the country of incorporation and third are the wealth taxes recently promoted in the last Free Lunch newsletter.

great article as always. Well done Martin!

Either the means of production are owned directly or indirectly by a few (capitalists), who make the economy work to enrich themselves, or we have the means of production socially/commonly owned through participatory democracy (socialism), & we have an economy designed to meet the needs of all.

@duvinrouge Just wondering - do you have a pension?

After neoliberalism had been rolled out globally, it became apparent that it doesn’t actually work.

They have made so many changes it’s almost impossible to identify where the problems are.

A highly interconnected global economy is a very complex system, how do we identify the cause of the problems?

The Right were always ready if things went wrong. They liked the right wing economics, but weren’t very keen on the more liberal aspects of this ideology.

They knew just where to place the blame when things went wrong.

Neoliberals tried to pretend there was nothing wrong for a long time, but now they need to identify the problems and it ain’t going to be easy.

The Right have made the most of the opportunity, but neoliberals had never even entertained the idea there might be something wrong with their ideology, we call it hubris.

@Sound of the Suburbs why doesn't it work? It lifted hundreds of millions out of misery. It works just fine.

Or is it the fact that you can't do a job that requires no brains and make 10x the average global income anymore... well, here's a world's smallest violin for that ~

While this article presents many interesting pieces of information about the development of western capitalism, I suspect that it also demonstrates a wilful lacuna in Martin Wolf's thinking - returns on assets. In particular, I note the absence of capital from the following sentence: "In this case “rent” means rewards over and above those required to induce the desired supply of goods, services, land or labour."

I believe that the idea is that some level of "normal" profit should be paid to capital to induce its supply.

Here, I wonder if there is a link with apparently excessive returns on equity and my criticism of excessive monetary policy easing. I have long suspected that impatient monetary easing, especially in response to a financial crisis, leaves a sense of overhanging incomplete fallout (eg as bad assets emerge), which deters investment. It occurs to me that the result is economies running with low capital stock, and hence, while that feared final leg of the crisis does not occur, a situation in which the on-going return on existing equity is high (because the market is discounting a significant risk of a bad period in the not too distant future).

This comment has been removed

This comment has been removed

The global financial system is a huge scam to take from the poor and give to the rich.

@Frank Jaeger

Yet somehow global poverty and global inequality are falling rapidly.

@RiskAdjustedReturn @Frank Jaeger That's mostly due to China.

@Ernst Stavro Blofeld @RiskAdjustedReturn @Frank Jaeger

Well, yes, due to China moving toward a market system.

When they were pursuing equality they didn't do too well.

This comment has been removed

Agree or disagree, there's a lot to mull over in this article. Martin Wolf articulates the problems of our day. It is no doubt one of his best works of the year for the FT. Bravo!

Add this to the mix:

“In the 1950s, a typical CEO made 20 times the salary of his or her average worker. Last year, CEO pay at an S&P 500 Index firm soared to an average of 361 times more than the average rank-and-file worker, or pay of $13,940,000 a year, according to an AFL-CIO’s Executive Paywatch news release today.” ( Forbes May 22, 2018)

@Joe Johnson

"$13,940,000 a year"

Wouldn't even make it onto the list of the 100 highest paid athletes.

https://www.forbes.com/athletes/list/3/#tab:overall

@RiskAdjustedReturn @Joe Johnson So does than mean that athletes are over paid and should be included in the index?

@practical investor @RiskAdjustedReturn @Joe Johnson

No, they're inexplicably exempt from public anger.

One of best articles by Mr Wolf for a long time. Essential reading to understand the causes of today’s problems

@Globalvillage It is but one opinion of today's problems. But it is significant that an FT write, one of significance is taking a step in this direction. Particularly significant given the lengths that some of Wolfs colleagues go to defending the liberal order and the part played in bring down on us the rise of nationalism and populism.

IMHO it does not rope in the part played by CB and to big to fail policies.

It’s called capitalism for a reason. It’s purpose is to enrich capitalists. We could have laborism, I suppose, but we don’t.

And exploitation of the have nots by the haves is neither new or unique to capitalism. It has been a feature of every “ism” for millennia.

I don’t think learned lectures by wise men like Martin Wolf will make much difference. History has had many cycles of wealth concentration and divergence. It will have more.

@Teton Pass

"We" will have what we want, not what a purely economic theory tells us.

"We" have often imposed "Our" will on the capitalist system: think anti-trust laws, consumer protection laws, limited copyright periods (ant-competitively extended as they are now), &c.

So, no, "we" don't need or want the debased and rent-based aspects of capitalism that currently afflict us, ands if a different tax regime and greater regulatory controls are the way to eliminate or reduce this social cancer, then that is what "we" will vote for.

One can already see the transformation in political debate, even tho Trump?Johnson prefer to dig deeper into the hole that is excess privilege to rentier.s

@Paulshk @Teton Pass We are not at full employment:

https://qz.com/1414865/the-us-unemployment-rate-is-at-a-48-year-low-so-why-are-so-many-americans-still-out-of-work/

And that's before factoring in high levels of involuntary part-time employment.

@Teton Pass If you ponder about how best to preserve and grow you capital one of the conclusions you must come to is that strangling off a large proportion of society, by rigging the system to favor one group over another, is not going to be helpful in your endeavor in the long run. Firstly you're burning off potential customers of businesses and thus reducing the potential of your business this is not capitalism, a la Henry Ford. Secondly, alienating a portion of society against capitalism will eventually, once the alienated group become a significant voting block, bring about the voting in of policies that will be detrimental to capitalism and your capital. Thirdly, there is significant risk in the current form of capitalism, lets loosely call it that for sake of argument, that eventually the have not's come at you with pitch forks. Evening if your willing to accept all that as acceptable to maintain unfettered in pursuit of tilting the scales in favor of capital, a democracy will eventually overwhelm you ability to sustain your position through either ballet box or revolution.

We are living through peculiar times. We have near full employment. We are living thought a time of plenty (I say this because I noticed how my tenants on benefits, have accumulated so much 'stuff'). I recall growing up, that I never had as much, as they did. The internet, means we can enjoy any kind of music. Tehre is no waiting around to save up for a record. We are entertained by the web. If we are hungry, we can tap and app and order a pizza and it will arrive quickly. We can keep in touch with friends.

A tenant on my street (on benefits) even managed to organise a party with an inflatable bouncy castle for their one year old child. The pound shops and thrift shops, have goods which are of reasonable quality.

It is like a couple who decide to break up, despite not having any arguments or infidelity, decide things not perfect.Journalists are also to blame for this mood, as they only care about spreading bad news, as that sells papers

@Landlord

We have near full employment, but much higher levels of insecurity.

We have a systematic attack on what might offer greater security (in unemployment, old age, sickness, &c).

And we have widespread dislike of flat earnings for the many and outrageously high earnings for the few.

Plus a systematic grabbing of the reins of policy making by extremely well placed and well funded lobbyists.

Citizens united was the worst case ever decided by SCOTUS for the damage it did to democratic institutions and process.

This is not about negative journalism, it is about negative facts and experiences.

@Paulshk @Landlord

Unfortunately, there's no such thing as job security.

Regarding "flat earnings", the same earnings buy a constantly improving standard of living due to rapid advances in communications, medicine, etc.

Yes, I know -- land in London.

There are relative levels of job security.

And flat earnings do indeed buy us a higher standard of living, but not necessarily for the less than top 15% (sorry to insult you, as I am sure we are in the top 0.5%), but thaT IS NOT TRUE FOR THE RELEVANT DEMOGRAPHIC, POLITICALLY.

Sorry about caps.

The problem with parities Conservatives is that they want everything run by multi-nationals. The parties on teh left want everything run by local councils or the state. None of the political parties are looking our for the little guy. The economy is dominated by big business, but they have clever accountants to reduce their tax bill. So when Corbyn says increase taxes, it usually means to increase them on people already paying it.

Look at big shopping centres, they are dominated by multinational brands. Local councils trying to push out small businesses with parking charges or market stall being driven out by high rents as councils want to sell the land to developers.

Merger should be banned, as they lead to job losses and insecurity. Great for the CEOs who get a pay rise or a big pay off, but if your worked for 20 years in the same company and you loose your job due to a merger, it may be hard to get a new one.

Today's rich are not longer people, but big corporations. Apple decide to sell their iPhone, via CarephoneWarehouse, why not sell via small and independent mobile phone shops? They excluded the little guy from the biggest killer product in recent years.

Inheritance tax should be scrapped, so that people have money to start businesses. They should tax the trappings of wealth e.g. sports cars, jewellery, furs, branded clothing etc...

They also need to have a freeze on house prices at 2019 levels, so that wages can catch up.

Call Centres make people feel powerless, especially if they can't get things done or are being stone walled.

Amazon is wiping out the competitors, with their low pricing.

Very well and clearly said, Mr. Wolf.

A functioning capitalist system is about allocation of resources. This is just a fraction of social interaction and, therefore, capitalism needs a coherent regulatory framework. After the fall of the soviet union our authorities were simply overwhelmed and put regulation at the mercy of dogmatic beliefs. A direct result was financial deregulation domestically and opening of capital accounts internationally based on a view that financial transactions by themselves would improve productivity. Of course, they could do that only to a very limited extent as productivity is about innovation and eg betting on the Yen versus USD in a variety of forms is not innovation. By the time Mr Greenspan was firmly in his driving seat at the Fed we were told that CB have the ability to preempt recessions, ie act on interest rate policies before something happens. We were also told that CB not only could foresee events and act on them in advance but could foresee the results of the preemptive policies ... and preempt those as well. The result were too low interest rates that build up bubbles which ultimately resulted in the 2008/ crisis. Some of the crisis management measures - ZIRP and QE - were right, the bank bailouts contentious. Latter solidified moral hazard in the financial sector, financial oligopolies 'too big to fail' and a range of regulations that effectively made financing of SMEs and real economy projects much more difficult while increasing the oligopolistic power of large incumbents. The protracted ZIRP and QE beyond the crisis then did only two things: asset price appreciation with known distributional consequences and little 'trickle down' and the distortion of the price of money, the ultimate price on which all other prices, without exception, depend. Interfering with the price of money on a long term basis means interfering with the business cycle. Manipulating interest rates long term means creative destruction cannot occur and overcapacity (aka deflation) perpetuates. A further boost to incumbents over new entrants. In an economy that is regulated based on voodoo dogma rather than pragmatic evidence competition, innovation, equality and finally productivity growth are subdued. Some have been saying that this price was worth paying to avoid a 1930s type depression. One can say that every time a recession is in sight and I'm sure we will do more each time out of fear that the next crisis will be even harder given higher deficits and higher debt, lower starting interest rates and productivity. But the argument itself is disingenuous. 1929 is associated with long lines of unemployed without any safety net whatsoever. This cannot happen today as social security was built over 90 years precisely to avoid this scenario to unfold. Today's 1929 means huge budget deficits created mainly by automatic stabilizers - US deficit in 2009 shot up to 10% of GDP - more debt issued and a range of bankruptcies including of banks. Even for the latter we have systems and institutions in place - eg called FDIC - that can manage systemically important enterprises. The CB can accommodate and support all these measures during the crisis months. In 1929 there was no CB, FDIC, social security to speak of. We have to admit at some stage that we were afraid to lose money, to have lower living standards for a few quarters, panicked and were ready to accept long term costs - including rentier capitalism - for short term gain. We have also to admit that the overall costs of this stance are huge and we might have to review it.

Paragraphs

@Wheat beer ...and concision.

@Miles TLDR

Superb analysis!

Radical tax reform is essential in my view and part of the solution. Eliminate corporate tax (profit as a tax base has become unworkable) and replace it with user fees for all corporates to pay for the public goods they benefit from, i.e. “security, legal systems, infrastructure, educated workforces and sociopolitical stability”.

(And remove the money creating ability of banks, restricting that right to central banks only).

These are some ideas to start with - admittedly quite radical - but minor tweaks won’t get us there. I hope that the BRT CEO’s will start proposing and supporting radical change as a next step after their good start announcing a new era for corporate purpose.

@The Dad Is n't there a tax called VAT?

@Landlord @The Dad yes and its regressive.

@The Dad

Exactly. Forget about trying to chase profits around.

Tax companies on what they do in your country.