The Rich Get Even Richer

By STEVEN RATTNER

March 25, 2012

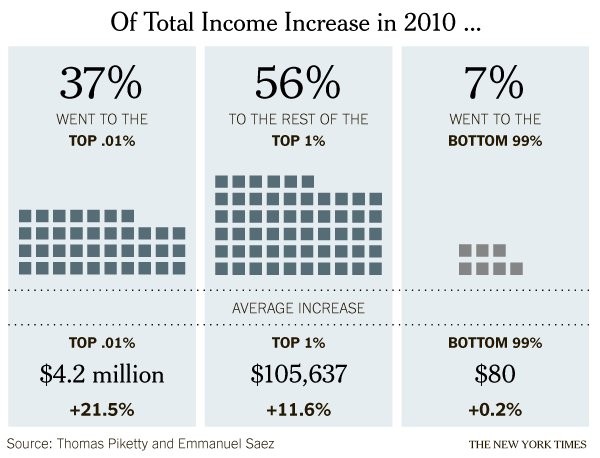

NEW statistics show an ever-more-startling divergence between the fortunes of the wealthy and everybody else — and the desperate need to address this wrenching problem. Even in a country that sometimes seems inured to income inequality, these takeaways are truly stunning.

In 2010, as the nation continued to recover from the recession, a dizzying 93 percent of the additional income created in the country that year, compared to 2009 — $288 billion — went to the top 1 percent of taxpayers, those with at least $352,000 in income. That delivered an average single-year pay increase of 11.6 percent to each of these households.

Still more astonishing was the extent to which the super rich got rich faster than the merely rich. In 2010, 37 percent of these additional earnings went to just the top 0.01 percent, a teaspoon-size collection of about 15,000 households with average incomes of $23.8 million. These fortunate few saw their incomes rise by 21.5 percent.

The bottom 99 percent received a microscopic $80 increase in pay per person in 2010, after adjusting for inflation. The top 1 percent, whose average income is $1,019,089, had an 11.6 percent increase in income.

This new data, derived by the French economists Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez from American tax returns, also suggests that those at the top were more likely to earn than inherit their riches. That’s not completely surprising: the rapid growth of new American industries — from technology to financial services — has increased the need for highly educated and skilled workers. At the same time, old industries like manufacturing are employing fewer blue-collar workers.

The result? Pay for college graduates has risen by 15.7 percent over the past 32 years (after adjustment for inflation) while the income of a worker without a high school diploma has plummeted by 25.7 percent over the same period.

Government has also played a role, particularly the George W. Bush tax cuts, which, among other things, gave the wealthy a 15 percent tax on capital gains and dividends. That’s the provision that caused Warren E. Buffett’s secretary to have a higher tax rate than he does.

As a result, the top 1 percent has done progressively better in each economic recovery of the past two decades. In the Clinton era expansion, 45 percent of the total income gains went to the top 1 percent; in the Bush recovery, the figure was 65 percent; now it is 93 percent.

Just as the causes of the growing inequality are becoming better known, so have the contours of solving the problem: better education and training, a fairer tax system, more aid programs for the disadvantaged to encourage the social mobility needed for them escape the bottom rung, and so on.

Government, of course, can’t fully address some of the challenges, like globalization, but it can help.

By the end of the year, deadlines built into several pieces of complex legislation will force a gridlocked Congress’s hand. Most significantly, all of the Bush tax cuts will expire. If Congress does not act, tax rates will return to the higher, pre-2000, Clinton-era levels. In addition, $1.2 trillion of automatic spending cuts that were set in motion by the failure of the last attempt at a deficit reduction deal will take effect.

So far, the prospects for progress are at best worrisome, at worst terrifying. Earlier this week, House Republicans unveiled an unsavory stew of highly regressive tax cuts, large but unspecified reductions in discretionary spending (a category that importantly includes education, infrastructure and research and development), and an evisceration of programs devoted to lifting those at the bottom, including unemployment insurance, food stamps, earned income tax credits and many more.

Policies of this sort would exacerbate the very problem of income inequality that most needs fixing. Next week’s package from House Democrats will almost certainly be more appealing. And to his credit, President Obama has spoken eloquently about the need to address this problem. But with Democrats in the minority in the House and an election looming, passage is unlikely.

The only way to redress the income imbalance is by implementing policies that are oriented toward reversing the forces that caused it. That means letting the Bush tax cuts expire for the wealthy and adding money to some of the programs that House Republicans seek to cut. Allowing this disparity to continue is both bad economic policy and bad social policy. We owe those at the bottom a fairer shot at moving up.

Correction: March 26, 2012

Due to a typo, an earlier version referred incorrectly to the distribution of income gains made during the Clinton expansion. Forty-five percent of the total income gains went to the top 1 percent, not to the top 11 percent.

Steven Rattner is a contributing writer for Op-Ed and a longtime Wall Street executive.

The Vicious Circle of Income Inequality

By ROBERT H. FRANK

January 11, 2014

Danny Schwartz

Almost every culture has some variation on the saying, “rags to rags in three generations.” Whether it’s “clogs to clogs” or “rice paddy to rice paddy,” the message is essentially the same: Starting with nothing, the first generation builds a successful enterprise, which its profligate offspring then manage poorly, so that by the time the grandchildren take over, little value remains.

Much of society’s wealth is created by new enterprises, so the apparent implication of this folk wisdom is that economic inequality should be self-limiting. And for most of the early history of industrial society, it was.

But no longer. Inequality in the United States has been increasing sharply for more than four decades and shows no signs of retreat. In varying degrees, it’s been the same pattern in other countries.

The economy has been changing, and new forces are causing inequality to feed on itself.

One is that the higher incomes of top earners have been shifting consumer demand in favor of goods whose value stems from the talents of other top earners. Because the wealthy have just about every possession anyone might need, they tend to spend their extra income in pursuit of something special. And, often, what makes goods special today is that they’re produced by people or organizations whose talents can’t be duplicated easily.

Wealthy people don’t choose just any architects, artists, lawyers, plastic surgeons, heart specialists or cosmetic dentists. They seek out the best, and the most expensive, practitioners in each category. The information revolution has greatly increased their ability to find those practitioners and transact with them. So as the rich get richer, the talented people they patronize get richer, too. Their spending, in turn, increases the incomes of other elite practitioners, and so on.

More recently, rising inequality has had much impact on the political process. Greater income and wealth in the hands of top earners gives them greater access to legislators. And it confers more ability to influence public opinion through contributions to research organizations and political action committees. The results have included long-term reductions in income and estate taxes, as well as relaxed business regulation. Those changes, in turn, have caused further concentrations of income and wealth at the top, creating even more political influence.

By enabling the best performers in almost every arena to extend their reach, technology has also been a major driver of income inequality. The best athletes and musicians once entertained hundreds, sometimes thousands of people at one time, but they can now serve audiences of hundreds of millions. In other fields, it was once enough to be the best producer in a relatively small region. But because of falling transportation costs and trade barriers in the information economy, many fields are now dominated by only a handful of the best suppliers worldwide.

Income concentration has changed spending patterns in other ways that widen the income gap. The wealthy have been spending more on gifts, clothing, housing, celebrations and other things simply because they have more money. Their extra spending has shifted the frames of reference that shape demand by others just below them, so these less wealthy people have been spending more, and so on, all the way down the income ladder. But because incomes below the top have been stagnant, the resulting expenditure cascades have made it harder for middle- and low-income families to make ends meet. Despite taking on huge amounts of debt, they’ve been unable to keep pace with community standards. Interest payments impoverish them while enriching their wealthy creditors.

But perhaps the most important new feedback loop shows up in higher education. Tighter budgets in middle-class families make it harder for them to afford the special tutors and other environmental advantages that help more affluent students win admission to elite universities. Financial aid helps alleviate these problems, but the children of affluent families graduate debt-free and move quickly into top-paying jobs, while the children of other families face lesser job prospects and heavy loads of student debt. All too often, the less affluent experience the miracle of compound interest in reverse.

More than anything else, what’s transformed the “rags to rags in three generations” story is the reduced importance of inherited wealth relative to other forms of inherited advantage. Monetary bequests are far more easily squandered than early childhood advantage and elite educational credentials. As Americans, we once pointed with pride to our country’s high level of economic and social mobility, but we’ve now become one of the world’s most rigidly stratified industrial democracies.

Given the grave threats to the social order that extreme inequality has posed in other countries, it’s easy to see why the growing income gap is poised to become the signature political issue of 2014. Low- and middle-income Americans don’t appear to be on the threshold of revolt. But the middle-class squeeze continues to tighten, and it would be imprudent to consider ourselves immune. So if growing inequality has become a self-reinforcing process, we’ll want to think more creatively about public policies that might contain it.

In the meantime, the proportion of our citizens who never make it out of rags will continue to grow.

ROBERT H. FRANK is an economics professor at the Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell University.

The Vicious Circle of Income Inequality

Study Finds Greater Income Inequality in Nation’s Thriving Cities

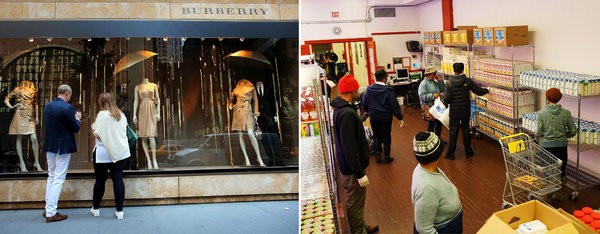

The luxury-goods store Burberry in Manhattan, left, and an emergency food pantry in Brooklyn illustrate income inequality in a city whose mayor, Bill de Blasio, has vowed to take it on.

Photographs by Spencer Platt / Getty Images

By ANNIE LOWREY

February 20, 2014

WASHINGTON — If you want to live in a more equal community, it might mean living in a more moribund economy.

That is one of the implications of a new study of local income trends by the Brookings Institution, the Washington research group. It found that inequality is sharply higher in economically vibrant cities like New York and San Francisco than in less dynamic ones like Columbus, Ohio, and Wichita, Kan.

The study, released on Thursday, comes as a number of cities across the country are trying to tackle income inequality and expand opportunity through measures like increasing the minimum wage, which President Obama has promised to do at the federal level. In no city is the effort more prominent than in New York, where the new mayor, Bill de Blasio, has promised higher taxes for rich families and better services for poor ones, including expanded early-childhood education and affordable-housing developments.

“The truth is, the state of our city, as we find it today, is a tale of two cities, with an inequality gap that fundamentally threatens our future,” Mr. de Blasio said this month, echoing his campaign speeches. “It must not, and will not, be ignored by your city government.”

Local officials here in Washington and in Boston, New Haven, San Francisco and Seattle have also seized on the issue.

But in some cases, higher income inequality might go hand in hand with economic vibrancy, the study found. “These more equal cities — they’re not home to the sectors driving economic growth, like technology and finance,” said its author, Alan Berube. “These are places that are home to sectors like transportation, logistics, warehousing.”

He added, “In terms of actual per capita income growth, these are not places that would be high up the list.”

That does not mean that measures intended to mitigate inequality will necessarily reduce the vibrancy of a local community. But the study confirms what many others have shown: The country’s big cities tend to have higher income inequality than the country as a whole. For instance, in the 50 biggest American cities in 2012, a high-income household — which the study measured at the 95th earnings percentile, putting it just into the top 5 percent — earned about 11 times as much as a low-income household, at the 20th percentile. Nationally, that ratio was 9 to 1.

Some places tend to have much more intense income inequality than others. A high-income family might earn 15 or 16 times what a low-income family earns in San Francisco or Boston, compared with earnings multiples of six or eight in places like Virginia Beach or Wichita.

Low-inequality cities, the study found, tend to be located in the South and the Midwest. They also tend to be geographically large, encompassing neighborhoods that in many other cities would be considered suburbs. Generally, the average for the top income group in such cities tends to be lower than it is in high-inequality cities — $150,000 to $200,000 a year, compared with $354,000 in San Francisco and $280,000 in Atlanta.

The driving force behind spiraling inequality at a national level is the rich getting richer. But in many cases, the Brookings numbers indicated, poverty is as important a factor at the local level. In Miami, for instance, a household in the bottom 20th income percentile earned just $10,000 a year in 2012.

Inequality in the 50 biggest cities grew modestly from 2007 to 2012, the study found. The effect was not primarily because of rapid income growth among the richest families — generally, earnings for the top 1 percent of the income distribution have not yet surpassed their prerecession peak. Rather, it was because poor families, saddled with debt and high unemployment rates, have suffered through the recession and the recovery.

The single biggest increase in inequality over that period occurred in San Francisco, where earnings for the typical low-income household dropped $4,000 and soared $28,000 in inflation-adjusted dollars for a high-income household. But in most other places, inequality intensified because the poor got poorer, including in Cleveland, Sacramento, Tucson and Fresno, Calif.

“High-income households did not lose much ground during the recession,” Mr. Berube of Brookings said. “Low-income households lost ground and haven’t gained it back. And the pressures around cost of living are higher at the low end than they are at the high end.”

Researchers say local inequality trends are related to national inequality trends, but are not the same. Any individual city’s earnings ratios might be more defined by who can afford to and wants to live there — whether a family of relatively low-skilled new immigrants, or a computer programmer in high demand or a financier from abroad — than by tidal economic trends like unionization and technological change.

But New York and many other cities have promised to tackle inequality, in part by shifting the tax burden, but also through initiatives aimed at attracting middle-class families with cheaper housing and better schools.

Study Finds Greater Income Inequality in Nation’s Thriving Cities

Income Inequality Is Not Rising Globally. It’s Falling

July 19, 2014

By TYLER COWEN

John Sposato

Income inequality has surged as a political and economic issue, but the numbers don’t show that inequality is rising from a global perspective. Yes, the problem has become more acute within most individual nations, yet income inequality for the world as a whole has been falling for most of the last 20 years. It’s a fact that hasn’t been noted often enough.

The finding comes from a recent investigation by Christoph Lakner, a consultant at the World Bank, and Branko Milanovic, senior scholar at the Luxembourg Income Study Center. And while such a framing may sound startling at first, it should be intuitive upon reflection. The economic surges of China, India and some other nations have been among the most egalitarian developments in history.

Of course, no one should use this observation as an excuse to stop helping the less fortunate. But it can help us see that higher income inequality is not always the most relevant problem, even for strict egalitarians. Policies on immigration and free trade, for example, sometimes increase inequality within a nation, yet can make the world a better place and often decrease inequality on the planet as a whole.

International trade has drastically reduced poverty within developing nations, as evidenced by the export-led growth of China and other countries. Yet contrary to what many economists had promised, there is now good evidence that the rise of Chinese exports has held down the wages of some parts of the American middle class. This was demonstrated in a recent paper by the economists David H. Autor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, David Dorn of the Center for Monetary and Financial Studies in Madrid, and Gordon H. Hanson of the University of California, San Diego.

At the same time, Chinese economic growth has probably raised incomes of the top 1 percent in the United States, through exports that have increased the value of companies whose shares are often held by wealthy Americans. So while Chinese growth has added to income inequality in the United States, it has also increased prosperity and income equality globally.

The evidence also suggests that immigration of low-skilled workers to the United States has a modestly negative effect on the wages of American workers without a high school diploma, as shown, for instance, in research by George Borjas, a Harvard economics professor. Yet that same immigration greatly benefits those who move to wealthy countries like the United States. (It probably also helps top American earners, who can hire household and child-care workers at cheaper prices.) Again, income inequality within the nation may rise but global inequality probably declines, especially if the new arrivals send money back home.

From a narrowly nationalist point of view, these developments may not be auspicious for the United States. But that narrow viewpoint is the main problem. We have evolved a political debate where essentially nationalistic concerns have been hiding behind the gentler cloak of egalitarianism. To clear up this confusion, one recommendation would be to preface all discussions of inequality with a reminder that global inequality has been falling and that, in this regard, the world is headed in a fundamentally better direction.

The message from groups like Occupy Wall Street has been that inequality is up and that capitalism is failing us. A more correct and nuanced message is this: Although significant economic problems remain, we have been living in equalizing times for the world — a change that has been largely for the good. That may not make for convincing sloganeering, but it’s the truth.

A common view is that high and rising inequality within nations brings political trouble, maybe through violence or even revolution. So one might argue that a nationalistic perspective is important. But it’s hardly obvious that such predictions of political turmoil are true, especially for aging societies like the United States that are showing falling rates of crime.

Furthermore, public policy can adjust to accommodate some egalitarian concerns. We can improve our educational system, for example.

Still, to the extent that political worry about rising domestic inequality is justified, it suggests yet another reframing. If our domestic politics can’t handle changes in income distribution, maybe the problem isn’t that capitalism is fundamentally flawed but rather that our political institutions are inflexible. Our politics need not collapse under the pressure of a world that, over all, is becoming wealthier and fairer.

Many egalitarians push for policies to redistribute some income within nations, including the United States. That’s worth considering, but with a cautionary note. Such initiatives will prove more beneficial on the global level if there is more wealth to redistribute. In the United States, greater wealth would maintain the nation’s ability to invest abroad, buy foreign products, absorb immigrants and generate innovation, with significant benefit for global income and equality.

In other words, the true egalitarian should follow the economist’s inclination to seek wealth-maximizing policies, and that means worrying less about inequality within the nation.

Yes, we might consider some useful revisions to current debates on inequality. But globally minded egalitarians should be more optimistic about recent history, realizing that capitalism and economic growth are continuing their historical roles as the greatest and most effective equalizers the world has ever known.

Tyler Cowen is professor of economics at George Mason University.

Income Inequality Is Not Rising Globally. It’s Falling

How Technology Could Help Fight Income Inequality

December 6, 2014

By TYLER COWEN

Rising income inequality has set off fierce political and economic debates, but one important angle hasn’t been explored adequately. We need to ask whether market forces themselves might limit or reverse the trend.

Technology has contributed to the rise in inequality, but there are also some significant ways in which technology could reduce it.

John Hersey

For example, while computers have improved our lives in many ways, they haven’t yet done much to make health care and education cheaper. Over the next few decades, however, that may well change: We can easily imagine medical diagnosis by online artificial intelligence, greater use of online competitive procurement for health care services, more transparency in pricing and thus more competition, and much cheaper online education for many students, to cite just a few possibilities. In such a world, many wage gains would come from new and cheaper services, rather than from being able to cut a better deal with the boss at work.

It is a bit harder to see how information technology can lower housing costs, but perhaps the sharing economy can make it easier to live in much smaller spaces and rent needed items, rather than store them in a house or apartment. That would enable lower-income people to live closer to higher-paying urban jobs and at lower cost.

Another set of future gains, especially for lesser-skilled workers, may come as computers become easier to handle for people with rudimentary skill. Not everyone can work fruitfully with computers now. There is a generation gap when it comes to manipulating electronic devices, and many relevant tasks require knowledge of programming or, more ambitiously, the entrepreneurial skill of creating a start-up. That, in a nutshell, is how our dynamic sector has concentrated its gains among a relatively small number of employees, thus leading to more income inequality.

This particular type of inequality may very well change. As the previous generation retires from the work force, many more people will have grown up with intimate knowledge of computers. And over time, it may become easier to work with computers just by talking to them. As computer-human interfaces become simpler and easier to manage, that may raise the relative return to less-skilled labor.

The future may also extend a growing category of employment, namely workers who team up with smart robots that require human assistance. Perhaps a smart robot will perform some of the current functions of a factory worker, while the human companion will do what the robot cannot, such as deal with a system breakdown or call a supervisor. Such jobs would require versatility and flexible reasoning, a bit like some of the old manufacturing jobs, but not necessarily a lot of high-powered technical training, again because of the greater ease of the human-computer interface. That too could raise the returns to many relatively unskilled workers.

A more universal expertise with information technology also might reverse some of the income inequalities that stem from finance. For instance, the returns from high-frequency trading were higher a few years ago, in part because few firms used it; now many firms can trade at very high speeds. It remains to be seen whether similar developments will lower hedge fund returns, but again it is possible to imagine a future in which many of the best investment and trading techniques are very widely copied and thus cease to be especially profitable.

A final set of forces to reverse growing inequality stem from the emerging economies, most of all China. Perhaps we are living in a temporary intermediate period when America and many other developed nations bear a lot of the costs of Chinese economic development without yet getting many of the potential benefits. For instance, China and other emerging nations are already rich enough to bid up commodity prices and large enough to drive down the wages of a lot of American middle-class workers, especially in manufacturing. Yet while these emerging economies are keeping down the costs of manufactured goods for American consumers, they are not yet innovative enough to send us many fantastic new products, the way that the United States sends a stream of new products to British or French consumers, to their benefit.

That state of affairs will probably end. Over the next few decades, we can expect China, India and other emerging nations to supply more innovations to the global economy, including to the United States. This shouldn’t be a cause for alarm. It will lead to many good things.

Since the emerging economies are relatively poor, many of these innovations may benefit relatively low-income Americans. India has already pioneered techniques for cheap, high-quality heart surgery and other medical procedures, and over time such techniques may achieve a foothold in the United States. Imagine a future China producing cheaper and safer cars, a cure for some kinds of cancer, and workable battery storage for solar energy. Ordinary Americans could be much better off, and without having to work for those gains.

To be clear, these are speculations and should not be taken as reasons to avoid improving our economy right now; furthermore, other trends may push in less positive directions. Still, these possibilities reframe the inequality problem. In the popular model developed by the economist Thomas Piketty, inequality is fundamentally about capital versus labor. In his view, capital has opened up an ever-widening lead because of the relatively high rates of return on savings and investment. The natural response to reverse this trend, according to Mr. Piketty, would be a direct attack on the return to capital, such as through a global wealth tax.

In the scenarios outlined here, though, growing inequality is highly contingent on particular technologies and the global conditions of the moment. Movements toward greater inequality often set countervailing forces in motion, even if those forces take a long time to come to fruition. From this perspective, rather than seeking to beat down capital, our attention should be directed to leaving open the future possibilities for innovation, change and dynamism. Even if income inequality continues to increase in the short run, as I believe is likely, there exists a plausible and more distant future in which we are mostly much better off and more equal. The history of technology suggests that new opportunities for better living and higher wages are being created, just not as quickly as we might like.

TYLER COWEN is a professor of economics at George Mason University.

How Technology Could Help Fight Income Inequality